Ferrari’s “completely revamped” 2024 Formula 1 car has stayed the same in one area that leaves Ferrari as a clear outlier compared to its main rivals.

The new Ferrari SF-24 is described by chassis technical director Enrico Cardile as a “big departure” from its first two cars of the ground effect era that started in 2022 and Ferrari is putting a huge emphasis on its aerodynamic work turning it into a title contender, having eschewed the pushrod rear suspension technical trend consciously adopted by every other team.

Red Bull technical chief Adrian Newey said from the start of the new rules in 2022 that optimising these low, stiff, ground effect cars is all about getting the underfloor and suspension to work in tandem.

Belatedly, other engineering chiefs have arrived at the same conclusion. So, a major focus for Red Bull’s main rivals across 2023 and now 2024 has been on suspension and platform control, with anti-dive and anti-squat features to keep the car more balanced and more consistent aerodynamically when exposed to the most extreme forces under braking, acceleration, and high speed.

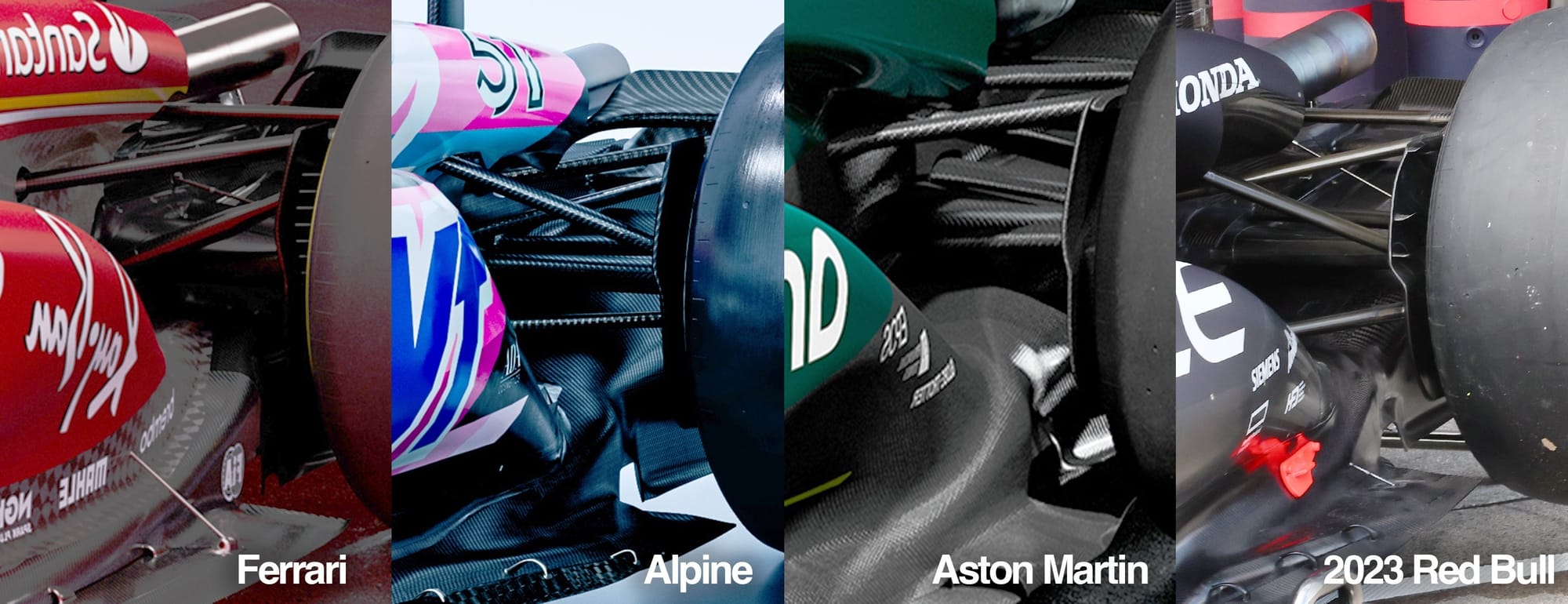

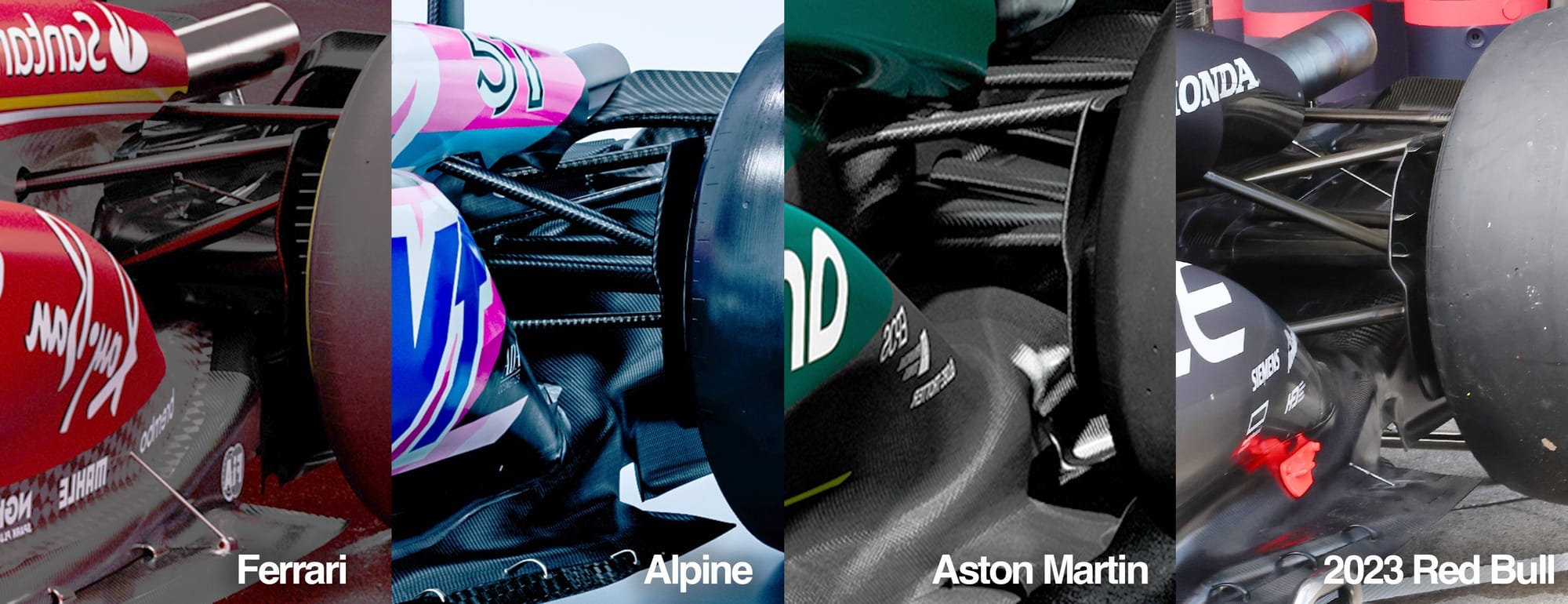

The convergence on pushrod rear suspension comes from the fact it provides better aerodynamic opportunities as it moves a key element out of the way for cleaner airflow to the diffuser and rear wing area, and frees up some space at the lower front of the gearbox, which can be useful for packaging.

But Ferrari is refusing to go in that direction. Its SF-24 stays with pushrod at the front and pullrod at the rear, making Ferrari the only team consciously choosing the pullrod rear configuration. Its customer Haas must follow suit because it takes that part from Ferrari.

The Red Bull teams, McLaren, Alpine and even Ferrari customer Sauber were already using pushrod rear suspension. Mercedes has now made that switch as well, based on what we saw from the new Aston Martin, which uses the Mercedes rear end – and unless Williams does something surprisingly dramatic, it should have the same.

Sauber is a particularly interesting case as it went to extremes in 2022 to have a pushrod design. While Ferrari supplies the gearbox internals, Sauber developed its own casing in order to be able to have its own suspension geometry design – complete with pushrod. That remains in place to this day as Sauber technical director James Key says while it’s a coin-toss whether you go pullrod or pushrod at the front, there’s a clear advantage to pushrod at the rear and it’s “purely for aerodynamics”.

Cardile says Ferrari investigated a pushrod layout but didn’t measure a big enough advantage to justify the compromises it thought there would be in terms of weight and compliance.

Instead, Ferrari is happy with how it has balanced those factors against aerodynamic performance with its existing layout – and doesn’t plan on changing that this year.

The suspension comes down to not just the fundamental configuration, but the geometries too, and Ferrari has added more anti-dive in the front and more anti-squat in the rear.

But Cardile admits that the front suspension is mostly a carryover from 2023. The rear has had more work done, likely in association with a shorter gearbox and slightly longer chassis. Cardile says: “The inboard suspension is differently located inside the gearbox, which has been an innovation.”

Clearly the suspension has been adjusted and optimised, but Cardile has something of a contrasting view to his peers. He said last season that suspension set-up is “a bit overrated”.

His argument was that aerodynamics dictate things more – from set-up options to tyre wear – and he suggested that the suspension “can play a role only if it’s bad”.

Ferrari clearly believes it is on top of its mechanical platform, so can prioritise aerodynamics. But it does also sound like Cardile has a fundamental difference of opinion about the relative importance of suspension in this generation of car.

And Ferrari is undeniably out on its own compared to its rivals. The question is this: is Ferrari right, and the configuration doesn’t matter as long as it all works, or has it baked in a fundamental performance limitation that won’t apply to its main rivals?